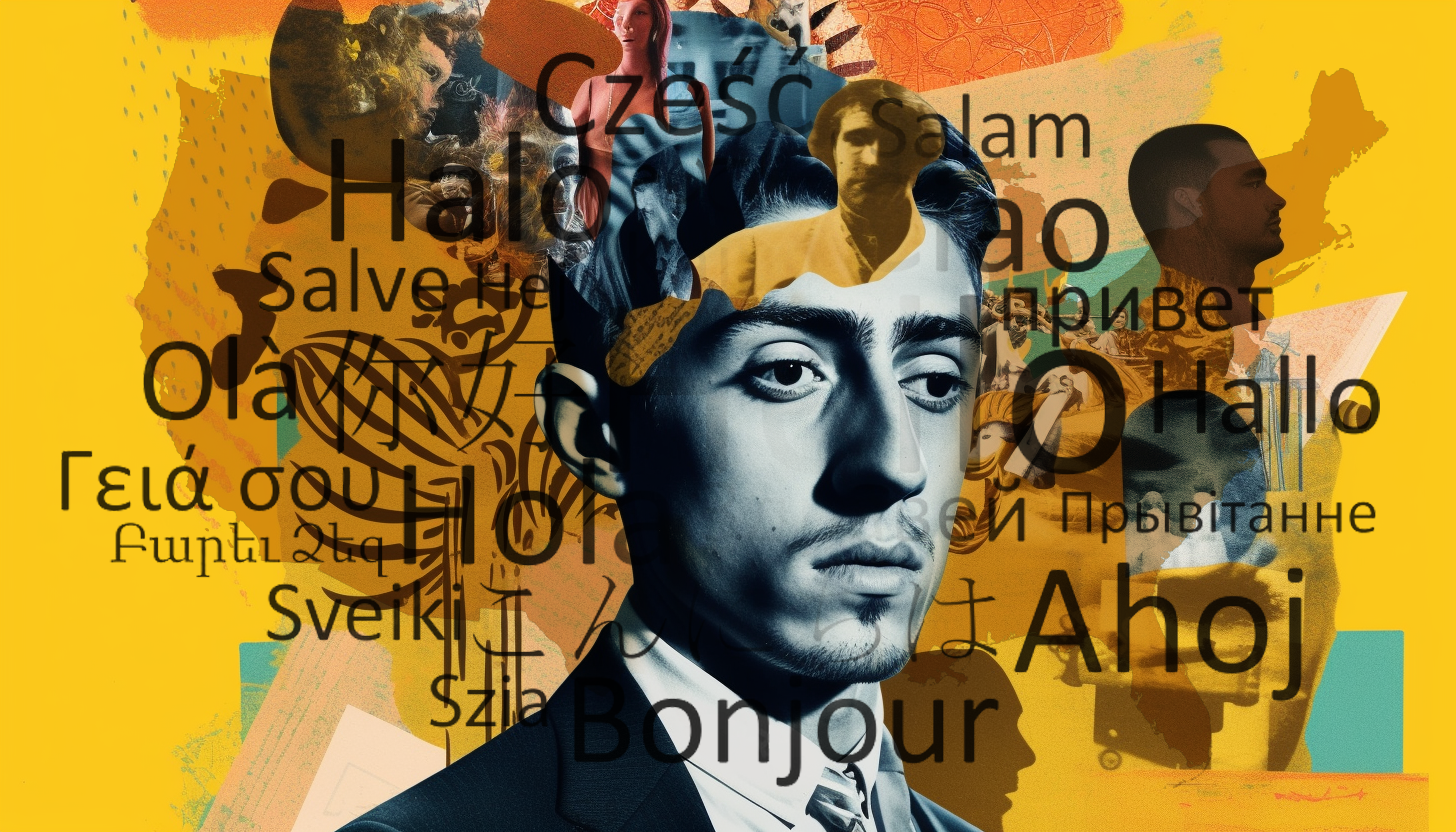

Much of the past six years of U.S. politics have been fundamentally driven by the country’s uncertain relationship with the burgeoning diversity of its citizens. The United States is at once a plural society bursting with multilingual, multicultural potential and an anxious country fretting over the perceived erosion of past cultural unanimity. If ours is a nation enriched by immigrants’ cultures and languages, it is also, as a 2017 American Academy of Arts and Sciences report put it, “stubbornly monolingual.”

How can we make the most of America’s plural riches? In partnership with The Children’s Equity Project, my Century Foundation colleagues and I recently published a report outlining the benefits of leaning into this national strength. As we write in the conclusion:

A plural, multilingual America is a smarter, stronger, richer—and more interesting—country. The United States is fortunate to have a large and growing population of linguistically and culturally diverse children in its schools. If policymakers commit to these children’s emerging bilingualism now with comprehensive investments in a more linguistically diverse teaching force and expanded access to dual-language immersion programs, they will have made a fundamental contribution to the health of our democracy.

America’s fraught relationship with its linguistic diversity is long-running, with pendular swings from periodically embracing to frequently erasing its multilingual heritage. For one, these lands host hundreds of indigenous languages from Yupik to Dakota, Ōlelo Hawai’i, Navajo, Sioux, and others. What’s more, many waves of immigration have brought the United States an enviable array of linguistic—and cultural—riches. American art, research, sports, cuisine, fashion, literature, technology, and music have been improved by millions of immigrants sharing the heritages of the countries and cultures of their birth.

The country’s unique pluralism is particularly valuable because it spans the global range of human civilization. A little over a century ago, Italian, German, Polish, and others reshaped American cities and smaller towns alike. Nearly fifty years ago, immigrants and refugees from Southeast Asia began to arrive in large numbers, bringing Vietnamese, Hmong, Khmer, and other languages to the United States. In the 1990s, immigration from Latin American countries increased, bringing Spanish—but also K’iche, Mixtec, Mam, and other languages.

Of course, these waves showed up in schools. At the beginning of the 20th century, roughly a quarter-million Midwestern children attended schools where they learned German. The country now boasts Hmong-English immersion charter schools and Vietnamese-English immersion district schools with the goal of preserving their children’s emerging bilingualism. Spanish-English bilingual education programs have long flourished in Texas, New York, and elsewhere.

And yet, Americans have not always embraced this unique national endowment. American jingoism put an end to most German-English bilingual schools by World War I, with many states banning German from campuses. This wouldn’t be the last time xenophobic opportunists fixated on multilingualism as a threat to the perceived American monoculture. Though the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Meyer v. Nebraska reversed these early twentieth-century bans on schools teaching in non-English languages—particularly German—they were later replaced by late twentieth-century bans on bilingual education for English-learning students in California, Arizona, and Massachusetts.

Pro-monolingual politicians routinely crop up whenever immigration rates increase. They follow a tired, predictable playbook: stoking the anxieties of voters—many of whom are direct descendants of relatively recent immigrants themselves—about how the latest round of newcomers threaten the stability of the American economy, society, and/or cultural core. The dubious premise behind this rhetoric—that there is a stable American “Way of Life” separate from constant enhancements by new, diverse cohorts of immigrants—is never examined.

Fortunately, as my colleagues and I write in our report, the pendulum has recently swung back towards a plural, polyglot democracy.

American enthusiasm for bilingual education—and bilingualism more generally—is unmistakably growing. Decades-old bans on bilingual instruction for linguistically diverse children were recently repealed in California and Massachusetts, and pressure for a similar move is growing in Arizona. Evidence suggests that family demand for dual-language immersion programs is often greater than the supply of seats—from Washington, D.C. to Gwinnett County, Georgia, to Portland, Oregon, and in hundreds of communities in between.

Whether families, educators, and policymakers know it or not, this enthusiasm has a substantial empirical backing from a wide range of fields—which we outline in detail in the report. Children who develop their emerging bilingual abilities gain unique cognitive, academic, social-emotional, and economic benefits. These are particularly pronounced for children who speak non-English languages at home—many of whom are designated as English learners by their schools.

Of course, these benefits are of little importance to politicians preying upon American anxieties about linguistic diversity. These folks care far less about what is best for linguistically diverse kids and far more about the power they can obtain by trumpeting about the primacy of English in America. Indeed, just a few months ago, conservative lawmakers launched a legislative effort to codify English monolingualism in federal legislation.

Trouble is, bilingualism’s benefits are collective as well. Economic forces continue to push the world towards global interconnection. The future belongs to countries best able to work across national and cultural lines of difference—which necessarily means working multilingually. As a longstanding immigrant destination country, the United States has inherent advantages navigating that new normal. The only question now is whether we’ll recognize—and learn to revel in—that strength.