For many years, I’ve been party to conversations with progressive donors and strategists about how to advance and then sell Democrats’ policy accomplishments. These conversations generally rest on two assumptions: (1) our policy views are correct and just need better messaging (the What’s the Matter with Kansas thesis), and (2) if not for obstructionism in Washington, Democrats would pass bold and transformative policy to lift up the marginalized. What’s stopping them, according to this line of thinking, is the filibuster, moderates in the Senate, the Supreme Court, and Republicans in the House.

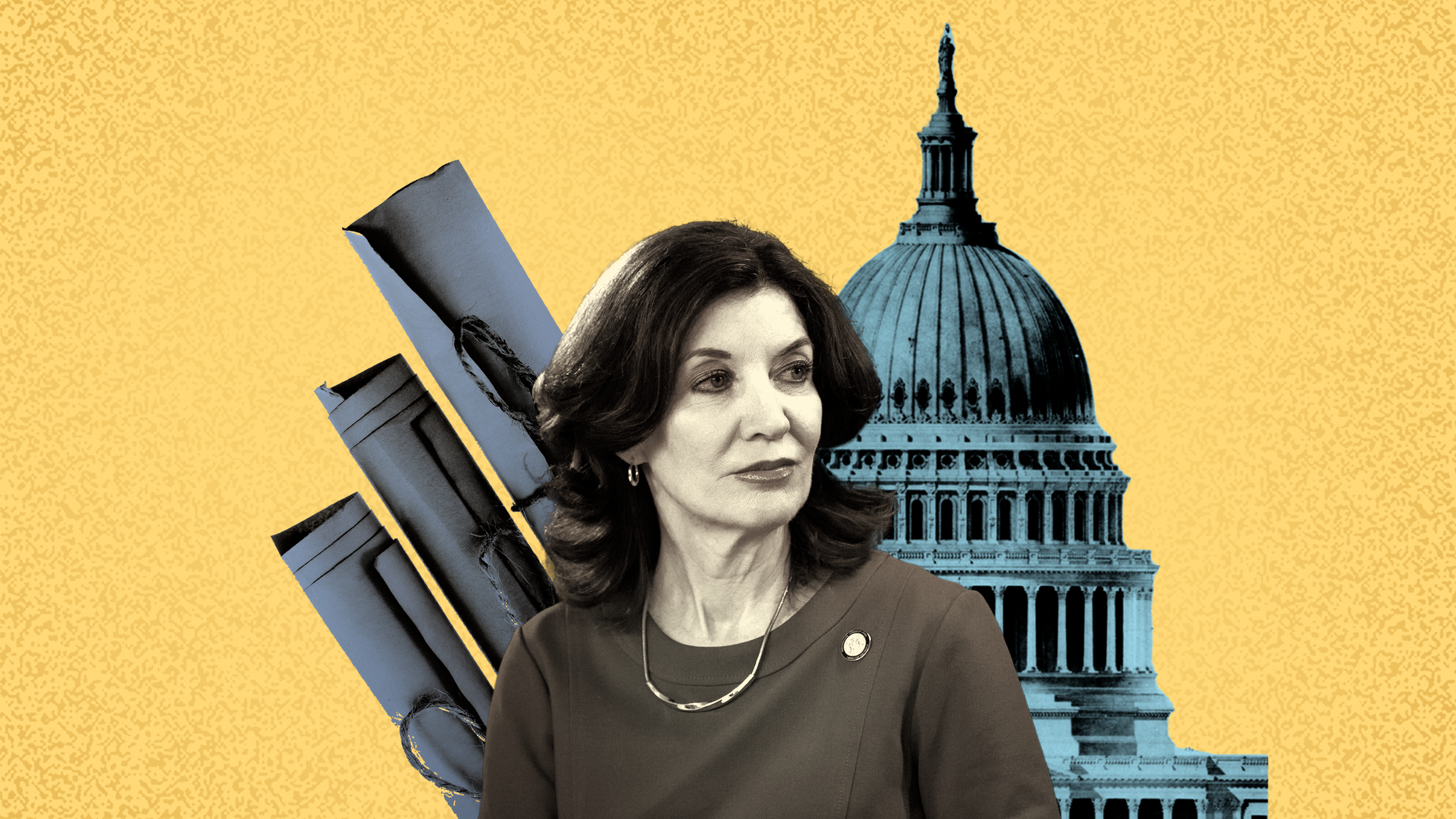

Now, I’m as appalled by obstructionism as anyone (and have devoted countless hours to the issue on the Majority 54 podcast), and I am a Democrat in part because I believe the party is more often right than wrong. But if the above two premises were true, then we’d expect to see incredible results in my home state of New York, where Democrats hold not just a trifecta of government control but a supermajority.

What have they done with this absolute power?

The NY legislature’s marquee moves on education this past year include passing a bill requiring New York City to reduce classroom size, blocking a proposal to dramatically expand small-group tutoring for students, and halting the expansion of public charter schools.

Class Sizes

The state is effectively mandating that New York City spend as much as $1 billion per year to cap class sizes at 20 students in K-3, 23 in 4-8, and 25 students in high school. This proposal was pushed by the leadership of the teachers union.

Most sensible people would want classes to be as small as possible, but we live in a world of limited resources. Is this the best use of money?

The data on the effects of class sizes is notoriously mixed. When Matt Barnum at Chalkbeat looked at available studies, he found that there’s “little rigorous evidence on how class size effects students in high school,” but quite a few studies showed modest results in elementary and middle school. The New York Times was even less impressed by the data:

An analysis of multiple studies found that the academic benefits of small classes are mixed. Generally, any academic gains for students are linked to relatively tiny classes, much smaller than what is required in the bill. . . Mr. Ready said the best evidence supporting smaller class sizes comes from studies in Tennessee and Wisconsin, where the classrooms studied had between 13 and 17 students.

Let’s assume there’s some modest benefit, in some grades, to reducing class sizes at the levels required by the New York law. The debate then becomes about the tradeoffs relative to other programs we could invest in. Here’s Barnum:

[T]hat doesn’t necessarily mean that New York’s class size cap is the right approach. The state is poised to force the city to choose reducing class sizes over other potential investments, and research doesn’t strongly support this either. Placing a hard cap on class sizes may also mean spending a lot to reduce class sizes in better-off schools, limiting the city’s ability to target resources to high-needs students.

This begs the question: if New York didn’t invest in a blanket class size reduction, what else would they invest in?

Tutoring

Sal Khan, in a recent TED Talk, cited data from 1984 that showed that small group tutoring can move a student from the 50th to the 95th percentile. Decades of studies since have confirmed that finding, including research by the Brookings Institution, which concluded that tutoring ranks among the transformative offerings a school district can make to families with struggling students. The think tank found that “over 80% of the 96 included studies reporting statistically significant effects.” Despite this data, Democrats in the legislature blocked $250 million put forward by Governor Hochul to help districts implement small-group tutoring.

This program would have cost a fraction of the total that New York City will spend annually to implement class size reductions. However, Democratic leaders from both chambers of the legislature inexplicably shut it down. It’s hard to tell why, though opposition from the New York Council of School Superintendents may have played a factor.

Charter Schools

New York has a statewide cap of 460 charter schools which has effectively prevented the issuance of any new charters since 2019. Governor Hochul proposed a series of measures that would lift that cap (though it’s complicated, read more here). Hochul faces stiff opposition both within the state legislature and the city council – as well as the teachers unions. As of today, Hochul is in a standoff over the budget with leaders of the Assembly and Senate who’ve both passed resolutions making clear their opposition to her charter school proposal. Even the city council, which has limited say in the matter, has come out against the proposal. This despite the fact that Democrats in the city support lifting the cap by a 24 point margin.

At a time where the Democratic Party is coalescing around a message of racial equity and championing difference, the best available evidence shows charters are a boon, primarily to Black and Latino students. In the 2018-19 school year in New York City, 62% of charter school students were proficient in math and 57% in reading, outperforming the traditional schools’ 45% and 47% respectively.

Critics often counter such data by claiming that charter schools “cream” students – meaning they recruit the higher performers and weed out the strugglers. But when the Stanford Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) compared “statistical match” students (ie, students with identical demographic, academic, and geographic characteristics), they found charter school students in New York City dramatically outperforming traditional public schools, with Black charter school students making nearly double the progress every year on reading and math than their zoned counterparts. This equates to receiving 23 additional days of instruction in reading and 57 days in math per year.

To sum it up, Democrats in New York this year passed a bill mandating an annual $1 billion spend on class size reductions based on anemic and often-contradictory research support, while rejecting two programs (tutoring and charter schools) which have for years produced jaw-dropping results. They did so largely because of adult politics: the unions love the class size cap and hate charters. The superintendents hate the tutoring expansion.

I helped elect many of these legislators – and without exception the candidates I worked with campaigned on platforms to help the vulnerable. These progressive politicians love to talk about kids, but when they get in a room with interest groups, they cave to raw political power. When I examine their record on the most important issue of the day – investing in our children – I am left wondering whether leaders of my party are truly worthy of the power we’ve given them.