This article originally appeared on Imbroglio. Imbroglio is a newsletter from The Branch about how we bring about the education revolution. Most of our posts will focus on the future of K-12 and higher education, but we’ll also cover the imbroglio itself — the politics, misdirection, the excuse-making, the mediocrity. Occasionally we’ll also meander into the general science of learning outside of the traditional education system.

I’ve split my professional life between two worlds.

In one world, I’ve been a loyal progressive operative—working for Obama’s first campaign and in his administration before founding and leading Arena, the most extensive training effort for Democratic campaign staffers in history. In another world, I founded and led a charter school network that primarily served low-income students of color in the South.

It’s always struck me how stark the difference is between how each of those worlds viewed the concept of school choice.

Most progressive operatives, donors, and luminaries I know will blanketly state that they oppose school choice. Nearly all of the fiercest opponents of charter schools I’ve faced were self-proclaimed liberals. Yet the Black and brown families I served in the Deep South were overwhelmingly in favor of school choice, as were our more conservative and moderate allies in the business community and state legislatures.

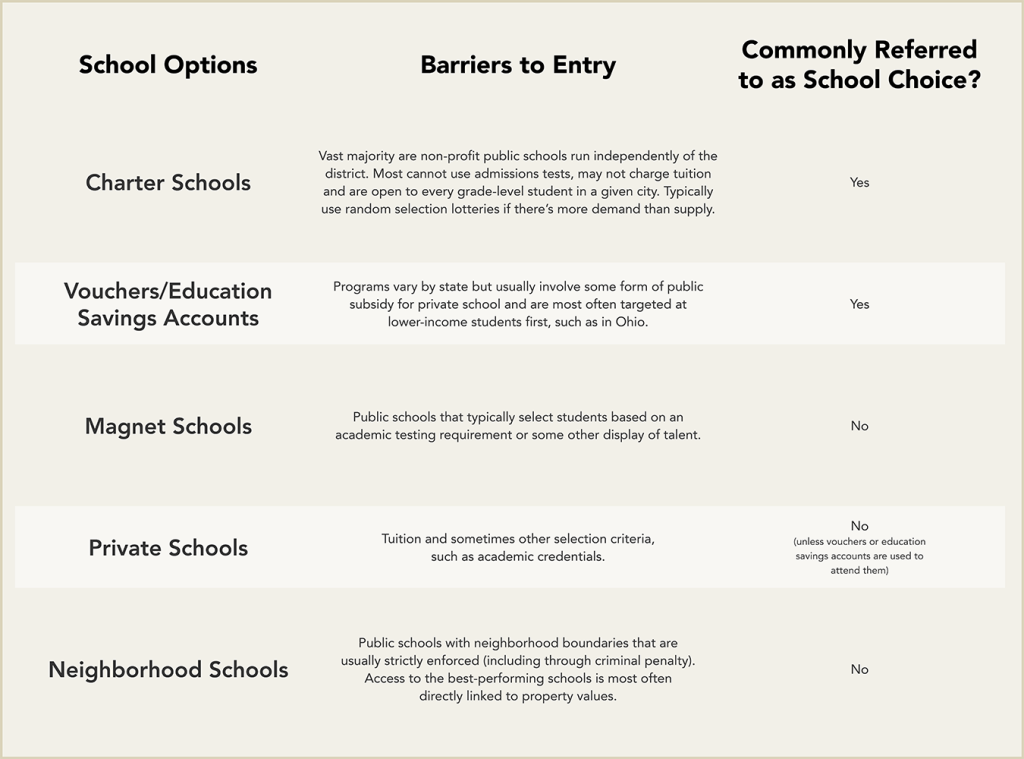

By and large, each of those groups exercises school choice when available. For Black and brown families, school choice most often comes through charter schools, vouchers, and educational savings accounts. For affluent white progressives, school choice comes in the form of private schools, magnet schools, and, most commonly, using their means to move to the “right” neighborhood with high-performing schools.

Need help following this? Here’s a nifty chart to help you track it all:

In each of these cases, parents have more than one schooling option. They make a choice. However, for some reason, we only use the term school choice when it involves the primary methods used by Black and brown families.

Of course, not all Democratic leaders are alike. President Obama and a handful of Democrats like Senator Cory Booker and Governor Jared Polis are more favorable to charter schools, and some governors like Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro and Illinois’ JB Pritzker have warmed to some forms of education savings accounts or private school scholarships. However, most prominent Democrats on the national stage over the past decade have been largely critical of charter schools and downright hostile toward vouchers and education savings accounts. (Note: We will discuss the performance of these voucher and education savings account programs on today’s episode of Lost Debate, which will drop on this feed later today and discuss charter school performance data on this episode.)

President Biden has stated, “I am not a charter school fan,” and moved to tighten restrictions on schools. Senator Bernie Sanders called for a blanket moratorium on public funding for new charter schools. Senator Elizabeth Warren also proposed killing federal funding for charter schools, even though she enthusiastically endorsed a form of vouchers before she ran for office. In Warren’s 2004 book The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Parents Are Going Broke, she wrote about the urgent desire of parents to “save their children from failing schools” and that “fully funded vouchers would relieve parents from the terrible choice of leaving their kids in lousy schools or bankrupting themselves to escape those schools.”

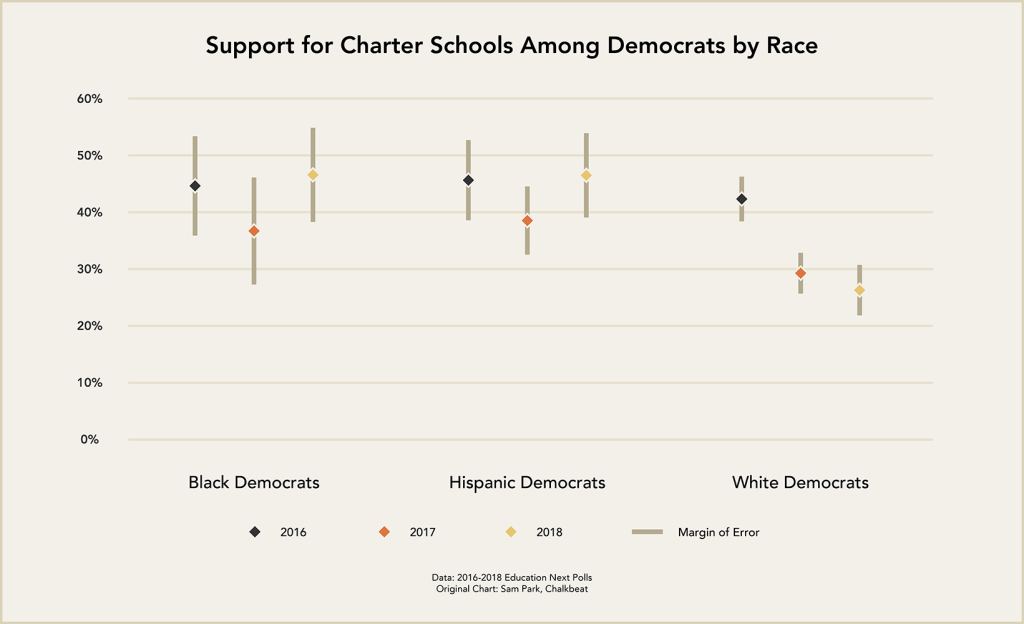

Warren’s reversal mirrors that of many white progressives, whose support for charter schools began to wane in the latter half of the Obama administration before precipitously dropping around 2016.

A poll from Democrats for Education Reform found an even more pronounced split by 2019, with a 26/62 favorable/unfavorable split among white Democrats versus a 58/31 for Black Democrats and 52/30 for Hispanic Democrats.

President Trump and Secretary Betsy Devos’ embrace of charters is undoubtedly a huge factor in this trend. Still, it’s notable that Black and Hispanic support for charters has remained constant during the same period.

What accounts for this divergence? These are, after all, members of the same party.

It all comes down to perceptions of different kinds of school choice. For many white progressives, their form of school choice is taken for granted and largely immune from criticism. They move to the right neighborhood with the shiny, high-performing school. They brag about sending their kids to “neighborhood schools.” They are “proud public school parents” who oppose “privatization” and claim to lock arms with parents from across town who also send their kids to their zoned schools.

This is all a rhetorical sleight of hand. The neighborhood schools being championed by the more privileged bear almost no resemblance to the experiences of those they claim to speak for. Here’s my friend, Neerav Kingsland, writing years ago for the Washington Post:

“For much of our nation’s history, neighborhood schools have been bastions of exclusion, not inclusion. And this exclusion persists to this day.

For every child who gets preferred access to a neighborhood school, there are many other children denied access to this same school. What is inclusive for one set of students is exclusive for a much larger set.

Historically, having neighborhood schools kept black students from learning alongside white students; poor students from attending school with wealthy students; immigrant students from studying with native-born students — and the list goes on.”

This isn’t just about history. Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren have quantified what it means to be lucky enough to live in the right neighborhood. They studied 7 million families who moved across commuting zones and counties, finding that neighborhood quality dramatically shapes a child’s earnings, college attendance rates, fertility, and marriage patterns. This dovetails with the work from Joseph G. Altonji and Richard K. Mansfield, who found that the difference between attending a ninetieth versus tenth percentile neighborhood school has life-altering effects on graduation rates and lifetime wages.

The problem for my fellow progressives is that they claim to speak for that 10th percentile but disproportionately draw their national elected leaders, operatives, and donors from the 90th percentile—something others like David Shor have pointed out. (The conservative commentator Cory DeAngelis pointed out that nearly all of the 2020 Democratic contenders either attended private school or sent their kids to private school, making them six times more likely than the average American to exercise private school choice. Yet every one of them opposed vouchers or education savings accounts.)

When many white progressives think of the neighborhood school, they picture Pleasantville. Kids walking to school on clean, safe streets and waving to the mailman. Glistening school buildings with a stable crop of experienced teachers and a healthy dose of enrichment programs and gifted and talented options. And if, God forbid, anything goes awry at that school, these parents will, without hesitation, place their child in a private school, lobby their way into the right magnet school, or simply move to a different neighborhood. Civil rights leader Howard Fuller put it colorfully: “A lot of folks who are hollering about neighborhood schools, left that neighborhood as soon as they had the money and the resources [to do so] and then they go out to wherever they are and holler back at us about how important these neighborhood schools are.”

What about everyone else? What about the parents who don’t have that luxury? Here’s Elizabeth Warren’s advice for them:

“If you think your public school is not working, then go help your public school. Go help get more resources for it. Volunteer at your public schools. Help get the teachers and school bus drivers and cafeteria workers and the custodial staff and the support staff, help get them some support so they can do the work that needs to be done. You don’t like the building? You think it’s old and decaying? Then get out there and push to get a new one.”

Warren, who herself sent her son to a private school (and lied about it when confronted by a Black mother), is telling parents it’s on them to fix their schools. Imagine if she’d made this argument about any other area of public policy. Imagine if she said this:

“If you think the health care system is not working, then go help your hospital. Go help get more resources for it. Volunteer at your local clinic. Help get the doctors and nurses and EMTs, help get them some support so they can do the work that needs to be done. You don’t like the emergency room? You think it’s old and decaying? Then, get out there and push to get a new one.”

If Warren stood on a debate stage and said this to a room of Democrats, she would be booed off the stage. It’s an ethic of pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps personal responsibility that would make Reagan blush. Yet when she talks like this about schools, it attracts little notice.

The Democratic Party leadership can only tolerate this cognitive dissonance for so long. At some point, those outside Pleasantville will start calling out this double standard. And when they demand change, my hope is for a new breed of politicians to rise up and lead the way to a more egalitarian future.