This article originally appeared on our substack

The 2022 primary season is underway, and like any election, there are safe seats and battlegrounds. In years prior, Missouri’s Senate race would be getting a lot of attention right now. It was once one of the country’s truest battlegrounds, a telling microcosm of American politics. For a century – between 1904 and 2004 – it was the nation’s most reliable bellwether, voting for the eventual president every time but once. The Show-Me State, more than any other state, could show you who was going to win the White House. It was uniquely attuned to the pulse of the nation.

Not anymore. There’s a contradiction here, yet it also adds up: Missouri has fallen out of touch while showing precisely how America’s voting patterns are changing. There are few such compelling demonstrations of a shifting, polarizing country.

The state’s crystal ball is buried in the geologic record of American politics, a fossil from the pre-polarized era. Today, Missouri’s no bellwether. It’s a case study.

Geographically, Missouri mirrors the country in a few ways. It’s predominantly rural, bracketed by dual population centers on its eastern and western borders. St. Louis and Kansas City are its “coasts.” Those two cities vote reliably blue and nearly always have, as do most comparable cities nationwide. Almost everything in the less densely populated middle now votes reliably red; again, true of much of the country today.

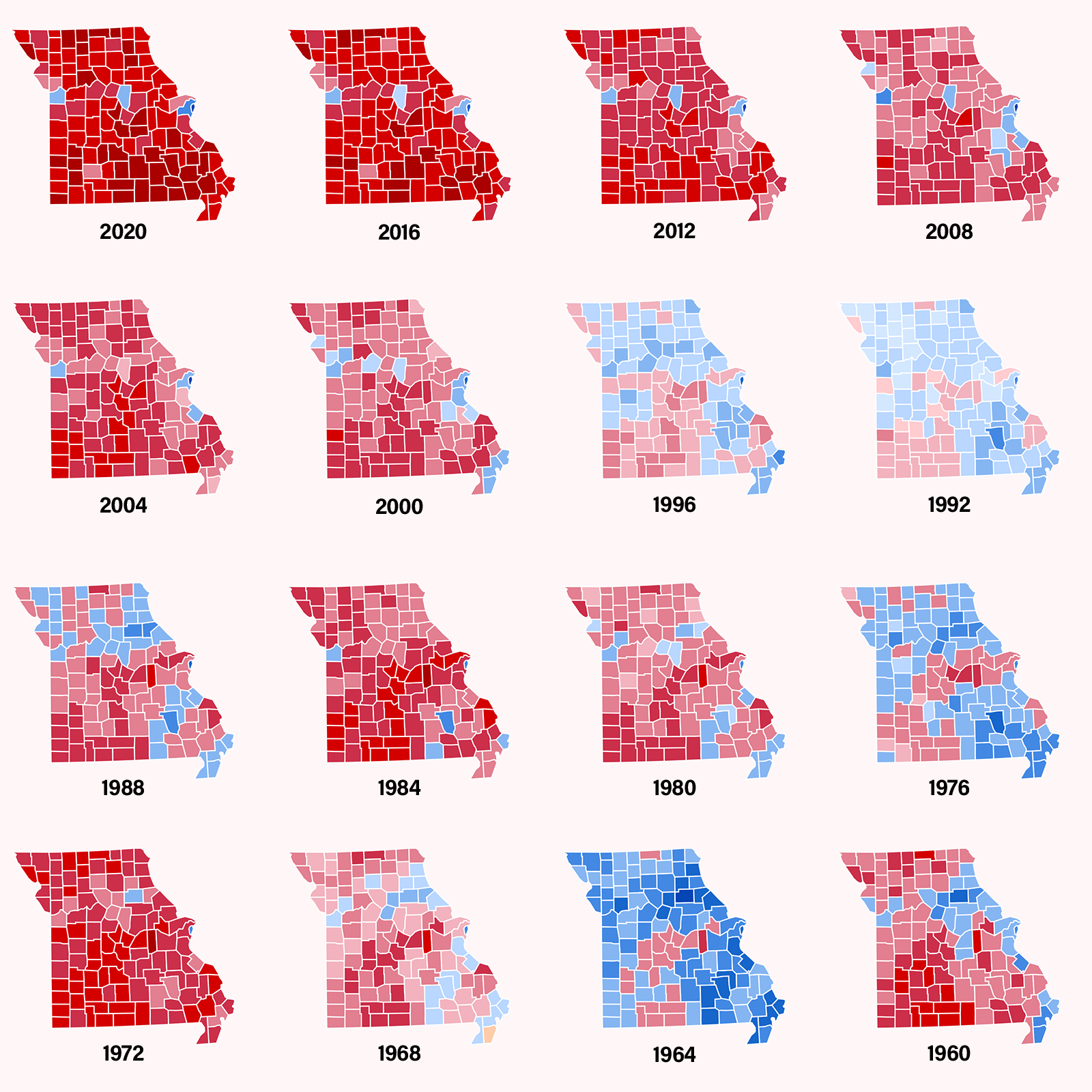

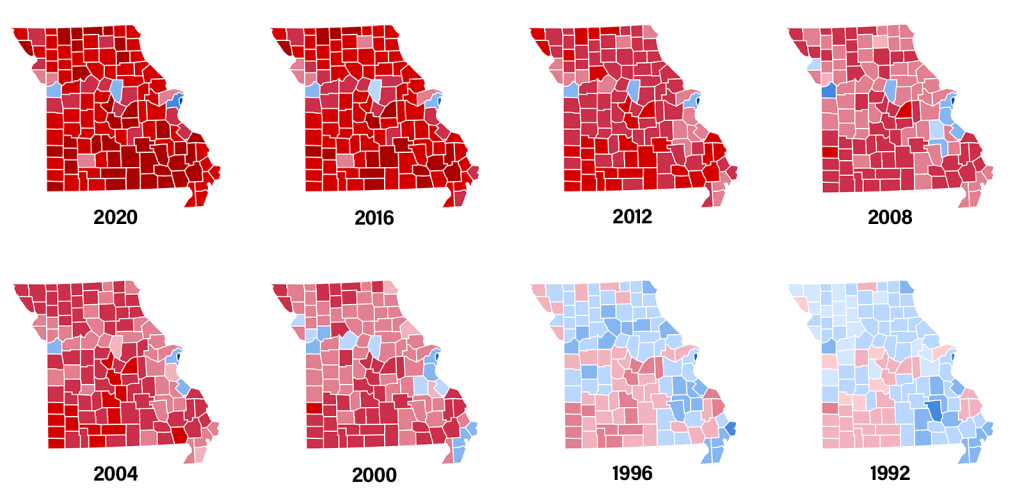

And yet, it wasn’t always. Watch how the state’s congressional counties change over time, starting from the last time a Democratic presidential candidate won the state: Bill Clinton.

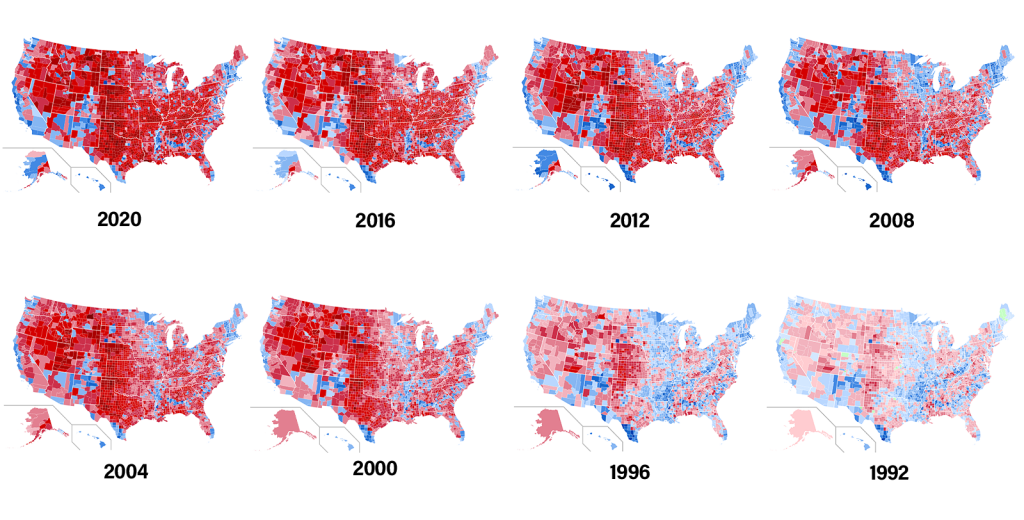

Now, watch a map of the whole country do something similar.

Missouri is a textbook case for how the rural-urban divide has changed our national politics, and the last few presidential races bear that out.

In 2008, Barack Obama lost Missouri to John McCain by 3,903 votes. It was the closest race in the country. History might’ve forgiven the state’s first misread in five decades, but by 2012, Missouri was further off than ever. Mitt Romney won the state by 9.38% while losing the national popular vote by 3.9%. Missouri’s turn to the right was official.

And yet, the turn wasn’t complete. Missouri correctly called the 2016 election, but the margin was a shock to the many pollsters who thought Hillary Clinton would hold onto more of the Missouri voters who had supported her husband twice in the 1990s. Trump carried Missouri by 18.5%, the state’s widest margin of victory since Ronald Reagan drubbed Walter Mondale in 1984.

Even then, Reagan drubbed Mondale everywhere. He won 49 of 50 states and only barely lost the one. It was a historic blowout, one mirrored in Missouri. That was the state’s magic: not only did it get the races right, it closely tracked the winner’s margin of victory.

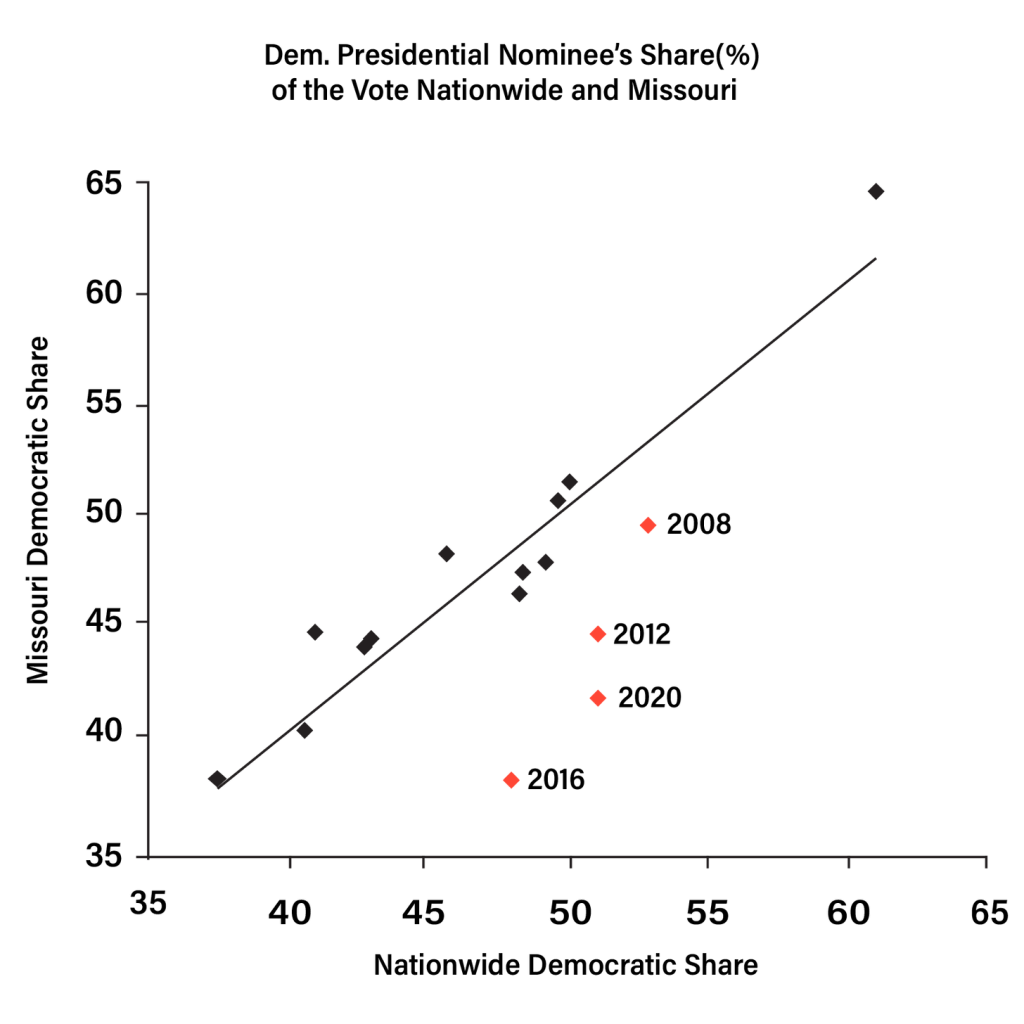

After Missouri’s one and only miss in 1956 (shoutout to Adlai Stevenson), in the twelve “presidential contests from 1960 to 2004, the Democratic nominee’s share of the Missouri vote fell, on average, 1.5% from his national share – a stunning degree of proximity,” writes Saint Louis University’s Ken Warren. “Over almost half a century, simply looking at the vote in Missouri did not merely provide a perfect harbinger of which candidate won the presidency, but it also offered an extraordinarily close approximation of the candidate’s national vote share.”

That discrepancy has dramatically widened from 2008 on, peaking in 2016. Trump-Clinton was a historic blowout in Missouri, but by no means the country. Trump lost the popular vote by 2.09%. In 2020, Missouri went for Trump again, far and away the widest miss of Missouri’s modern history. Trump won the state by 15.4% and lost the national popular vote to Joe Biden by 4.4%.

As these results add up, the question asks itself. What happened to Missouri the microcosm? What changed more? Missouri, or the America around it?

How Missouri Lost Its Touch

Even at the height of Missouri’s predictive powers, ‘bellwether’ may have been a misnomer. America is moving Missouri, not the other way around. It’s always been more of a weathervane, channeling the political winds of the country and reading them back. It’s still doing that in a sense, those winds just aren’t blowing the same way anymore.

The polarization of the nation has brought on massive political shifts in Missouri, all while the state, compositionally, hasn’t done much changing at all. It has roughly the same ingredients – i.e. people – that made it a finely tuned political radar for a century, and that’s part of the reason it’s on the wrong frequency now. The country is growing more diverse at a rapid pace. Missouri is not.

The latest census data puts the state at 79.1% white to the country’s 61.6%. The last time America was as white as present-day Missouri was some 30 years ago. The state isn’t adding many people at all, their race notwithstanding. Between 2010 and 2020, Missouri ranked 39th in population growth. It’s demographically stagnant.

Another part of the explanation, then, comes down to a bloc of Missourians that have always been there, but hadn’t always voted so reliably for one party: white evangelical Christians. That changed with the turn of the century, according to Warren. Republicans – following the lead of George W. Bush adviser Karl Rove – devoted their energy to turning out the evangelical vote. That strategy worked especially well in states like Missouri, awakening a powerful constituency that’s shown up for Republicans since.

In 2008, 39% of Missouri voters self-identified as evangelicals. Just 29% of them went for Obama. That was easily the difference between him winning and losing the state. That bloc then helped overwhelm successive Democratic tickets in 2016 and 2020, supporting Trump at a massive clip both times.

Still, even the evangelical vote doesn’t account for the whole gap. The other factor, argues Warren’s colleague Steve Rogers, was a restratification of political allegiances across the board. Missourians got with the times, changing their partisan allegiances accordingly. They re-sorted.

Partisan sorting is when voters choose the party that matches what they think of the world and themselves. What it means to be a Democrat today is not the same as it was 20 years ago, and the same goes for Republicans. Both parties have become more ideologically extreme, though notably not in the same ways.

There’s an endless list of reasons why, including, in no particular order: social media, echo chambers, identity politics, wedge issues, cable news, gerrymandering, tribalism, migration patterns, and the disappearance of the political middle.

We’re all impacted by that list to varying degrees. Our political environment shapes our ideas, even when we’re not necessarily aware of it. Rogers pointed me to a pithy line from the renowned political scientist Morris Fiorina, who once wrote that partisan identification “has an experiential basis. It is not something learned at mommy’s knee and never questioned thereafter.”

More and more Missourians are getting both the nature and the nurture at this point. Younger voters coming up now only have today’s climate as a frame of reference. They don’t remember a bellwether Missouri; the polarized present is all they know. The older voters that do remember aren’t swayed by bygone standards. They’re the ones doing the polarizing, owing to all manner of factors, largely because America’s political culture is pushing states like Missouri in that direction.

“As Republicans’ deft deployment of hot-button issues helped them dominate ancestrally Democratic northeast and southeast Missouri, the party’s center of gravity shifted right,” writes former State Senator Jeff Smith. “As Democrats lost rural Missouri and moderate Republicans lose the suburbs – speeded by the exodus of Trump-repelled women – the ideological middle continues to evaporate, since the most moderate legislators represented areas where their party’s brand is now tarnished.”

That process is playing out all over the country. Wedge issues – in Missouri, guns and abortion especially – are doing their job, driving Americans apart and into their respective foxholes. There are fewer and fewer close races on the horizon anywhere. Our battlegrounds are shrinking with each passing cycle, and they’re definitely not in Missouri.

Whichever Republican earns Trump’s endorsement is a good bet to go the distance. That will quite possibly be former Gov. Eric Greitens, despite his past and present controversies. GOP leaders are concerned about Greitens making a safe red state closer than it should be, and Missouri Republicans like Sen. Josh Hawley – instrumental in pushing Greitens to resign as governor four years ago – aren’t thrilled either.

That’s the kind of palace intrigue that would be plastered all over the national news if Missouri was even as competitive as Ohio anymore (another former battleground turning firmly rightward of late). If the race tightens up down the stretch, reporters will flock accordingly. As of now, the relative dearth of coverage seems to suggest that the candidate might not matter given the GOP’s edge in the state.

As for the presidential race, the only thing more powerful than a Trump endorsement would be a Trump candidacy. There’s no good reason to think Missouri would be the least bit competitive in 2024 if he enters the race as expected.

Like Fiorina says, none of this is necessarily static. Missourians could re-sort once again, but chances are that’s not going to happen on its own, nor anytime soon. The state remains a weathervane in that one key sense. For it to change, Missouri would need to see America change first. This is the Show-Me State, after all.