This article originally appeared on our substack

(The following is an excerpt from a forthcoming book I’m writing about America’s polarized politics)

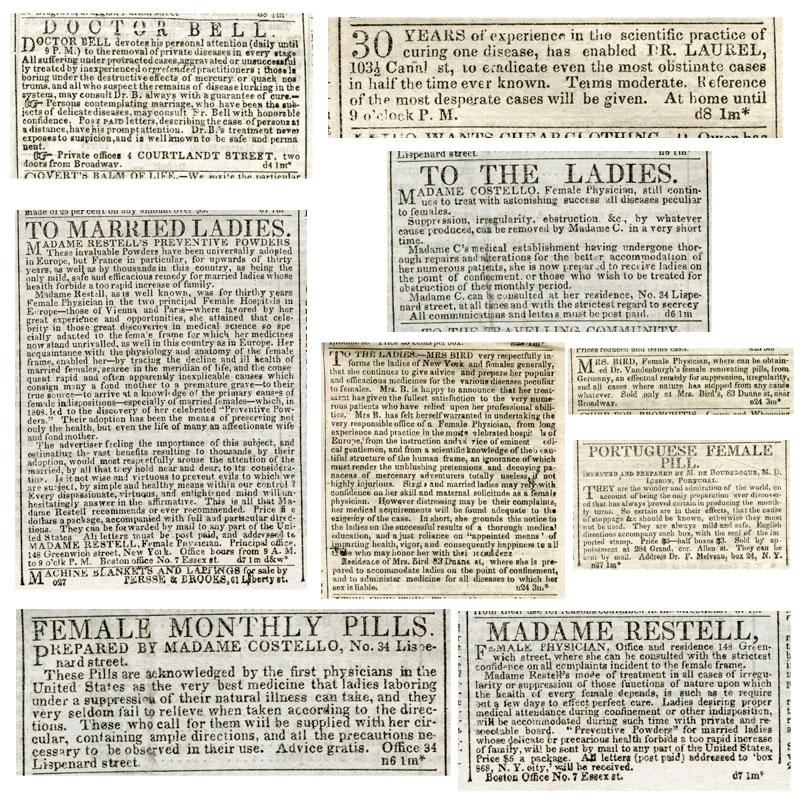

Our country has had a fraught relationship with the topic of abortion for a long time, but it took a while for it to reach center stage in our politics. From our nation’s founding through the early 1800s, abortion was largely unregulated. During this period, so-called “pre-quickening” abortions—before the woman could feel fetal movement—were customary enough to routinely show up in advertisements. Abortion was also common among enslaved Black women who wished to terminate pregnancies originating from rape and coercion from slave owners. These women even developed their own abortion drugs called abortifacients.

Around the mid-1800s, a movement of medical practitioners became concerned about the safety of abortion procedures, eventually leading to the American Medical Association in 1860 formally calling for an end to legal abortion. A growing number of states passed prohibitions, culminating in 1873 with the Comstock Law, which criminalized the publication of information on how to procure contraception or abortion.[1] Though there was a spirited debate about these laws, they were largely supported by a wide swath of American society, which possibly included famous women’s rights activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who, some historians have argued, publicly denounced abortion.[2]

By the early 20th century, every state classified abortion as a felony.[3] Yet the topic wasn’t a focus of politicians or law enforcement. Many physicians simply ignored the laws, performing almost a million abortions every year. The issue was largely non-partisan until well into the latter half of the century. The same could be said of contraception. The topic was so uncontentious that the conservative political icon Barry Goldwater served in the ’50s on the board of his local Planned Parenthood chapter.[4] And though President Gerald Ford supported restrictions on abortion, his wife as well as his Vice President were both pro-choice. Democrats were similarly difficult to pin down. Then-Democratic Senator Joe Biden voted for a constitutional amendment in 1982 that would let states overturn Roe v. Wade, citing his Catholic heritage.[5] An August 1972 Gallup poll found that 58% of Democrats and 68% of Republicans agreed that “decisions to have an abortion should be made solely by a woman and her physician.”[6] You read that right: Republicans were more supportive of abortion rights than Democrats of the time.

Abortion wasn’t the only issue that defied partisanship. The two parties either agreed on nearly every major policy or were similarly conflicted about them. It’s hard to believe, given today’s divisions, but until the past few decades, the common complaint about our political parties was how little separated them. In 1950, the American Political Science Association released a paper co-authored by many of the nation’s leading political thinkers who argued that the parties were too similar, worked together too easily, and allowed too much diversity of opinion within their ranks. “Unless the parties identify themselves with programs,” the authors cautioned, “the public is unable to make an intelligent choice between them.”[7] That harmony between the parties wasn’t just a reflection of the idyllic fifties. By 1976, when Jimmy Carter ran against Ford, just 54% of voters believed Republicans were more conservative than Democrats, and almost 30% said there was no discernible difference between the two parties.[8]

It’s tempting to feel nostalgia for those relatively unpolarized times. But they weren’t unambiguously positive. There was a dark side to the unity. As Ezra Klein has noted, “the activists and politicians who worked relentlessly, over years, to bring about the polarized political system we see today had good reasons for what they did.”[9] Often, voters were deprived of any real choice. That could mean no candidate opposed to the Vietnam War or supportive of any meaningful civil rights protections. One question I continually mull over is: “What is a healthy amount of disagreement?” When we say we want more unity, what do we mean? China and Russia have become increasingly unified as they’ve persecuted minorities, squashed dissent, and consolidated media in the hands of the government. I’d like to think we might find ourselves somewhere between the paralyzing divisions we have today and the homogeneity of the 1950s.

Abortion was the leading edge in the destruction of that unity of old. The major parties first mentioned abortion in their platforms in 1980, with Republicans opposed and Democrats in favor. Within a few years, abortion had risen to become the most polarizing policy topic since slavery.

How did abortion become so divisive so fast? Depending on who you ask, the issue was either the cause, catalyst, or symptom of a new era of polarization.[10] Harvard historian Jill Lepore is somewhere between the ‘symptom’ and ‘catalyst’ camps. “Making social issues into partisan issues took a great deal of work,” she writes in her landmark history text These Truths, adding, “much of it done by political strategists and well-paid political consultants.”[11] Lepore traces the roots of modern political propaganda to the 1930s—particularly to the eclectic duo of Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter, the Adam and Eve of campaign consulting. Whitaker and Baxter, a married couple from California, founded Campaigns Inc., the world’s first political strategy firm. They changed the course of American history in the process—successfully spinning for monopolies like Standard Oil and Dupont, and defeating universal healthcare both in California and nationwide. By the 1970s, an army of operatives expanded Whitaker and Baxter’s playbook, growing political consulting into a multi-billion-dollar industry that, in Lepore’s words, “divided the electorate by inciting outrage, having demonstrated that the more emotional the issue, the likelier voters were to turn up at the polls.”

It’s hard to imagine an issue more emotional than abortion. One side views it as the murder of children and the other views it as the infringement of bodily autonomy. The spin masters rightfully viewed this as the perfect wedge issue.

Many people blame the courts for abortion’s rise in prominence and trace the rise in division over the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision. Yet Lepore argues that many of the key players in the crusade against abortion were driven more by raw politics than from a sense of alarm over the decision. Southern Baptists, for example, had fought for the liberalization of abortion laws and had affirmed a resolution in 1976 that called for “legislation that will allow the possibility of abortion under such conditions as rape, incest, clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother.”

By 1980, key evangelical organizations such as the Southern Baptists and rising leaders in the Republican Party would not only change their stance on abortion, but make their opposition to it central to their identity. Ronald Reagan was a particularly effective vessel for this message, packaging defense of life in warmth and charisma, famously saying, “I’ve noticed that everyone who is for abortion has already been born.” Roe gave their side the most powerful weapon in politics: a grievance. In Lepore’s words, “politicians and political strategists needed these issues to remain unresolved: describing rights as vulnerable is what got out the vote.”[12]

At the time, Republicans had a massive advantage in both campaign technology and messaging skills. They adopted desktop computers well before Democrats did, using them to build sophisticated direct mail and telephone marketing campaigns. This in turn galvanized their voter base to donate to anti-choice candidates and causes and to reliably show up to the polls. One Republican direct mail guru estimated in 1980 that the GOP had more than double the amount of small dollar contributors over Democrats.

Within a few short years, abortion would become the litmus test for GOP candidates for office and appointees to the federal courts. That movement successfully placed a number of Roe critics on the Supreme Court, culminating in a fraught, razor-sharp 5-4 decision in the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. The decision upheld Roe (some would say begrudgingly), but signaled to liberals they were on precarious territory, prompting Democrats to more urgently match the political energy of the GOP on the issue. From that point forward, neither party would ever consider appointing a Justice or nominating a presidential candidate who wasn’t on the “right side” of the issue.

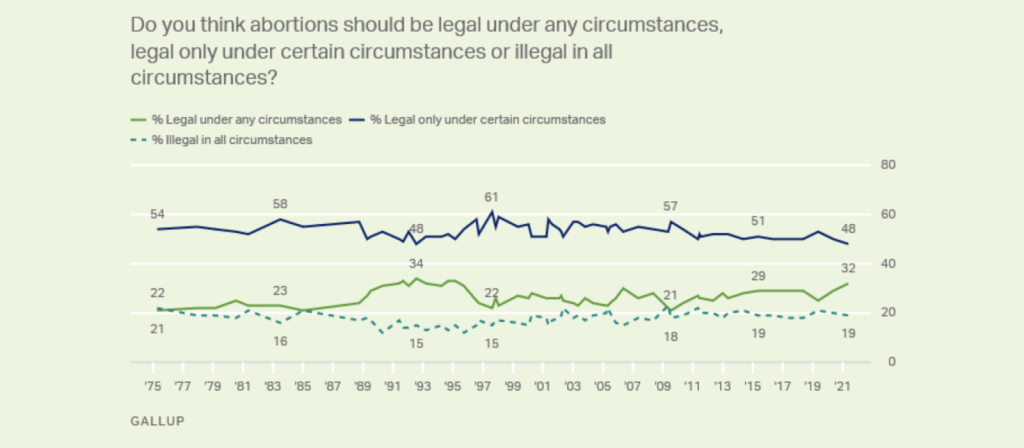

All of this happened as American views on abortion remained remarkably stable from the late 70s until recently.

Americans’ views didn’t change. It was their institutions that changed—particularly political parties, campaigns, and media outlets. A nearly complete self-sorting has taken place. Today, you can be almost certain of someone’s political party based on their opinion of Roe.

Of course, abortion isn’t the only issue that’s become fully polarized. Guns, immigration, and a whole host of other issues have become nearly as divisive. But abortion paved the way, serving as the testing ground for modern campaign and media strategies that have been driving us apart. We can think of it as our political ‘wedge issue zero.’ And, as hard as it is to believe, the recent news that the Court may be poised to overturn Roe means the issue may become even more politically salient.

[1] The law also, puzzlingly, criminalized information about sexually transmitted diseases.

[2] You’ll notice I hedged on my language a bit here. Some modern-day feminists dispute my characterization of Stanton and Anthony (https://time.com/4106547/susan-b-anthony-elizabeth-cady-stanton-abortion/) but the evidence is pretty clear to me that they would be considered pro-life by today’s standards, even if they weren’t animated by the subject in the way current activists are: https://slate.com/human-interest/2017/05/susan-b-anthony-anti-abortion-heroine-how-activists-are-claiming-her-for-their-own.html.

[3] Though some including exceptions for medical emergencies and in cases of incest and rape.

[4] Jill Lepore, These Truths, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018), 649.

[5] Anna North, “How Abortion Became a Partisan Issue in America,” Vox, April 10, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2019/4/10/18295513/abortion-2020-roe-joe-biden-democrats-republicans

[6]Jack Rosenthal, “Survey Finds Majority, in Shift, Now Favors Liberalized Laws,” New York Times, August 25, 1972.

[7] Towards a More Responsible Two-Party System: A Report of the Committee on Political Parties (Washington, DC: American Political Science Association).

[8] Morris P. Fiorina, Party Sorting and Democratic Politics, series no. 4, Hoover Institution, Stanford University, https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/fiorina_party_sorting_and_democratic_politics_4.pdf.

[9] Ezra Klein, Why We’re Polarized (Avid Reader Press, 2020), 2.

[10] I was reluctant to call this an era because eras have beginnings and ends. As I will discuss later in this book, I am not sure our divisions will ever recede.

[11] These Truths, 648.

[12] These Truths, 666.